A Story of Accessibility: Gender and Caste in the History of Yoga

Approximately 80% of practitioners of modern yoga are female-identifying. It has not always been thus. During my Master’s studies, I spent some time researching the roles of gender and caste in shaping early Indian religions, out of which modern yoga evolved, from the origins of Vedic Brahmanism, through the emergence of asceticism and of the Śramaṇa religions such as Buddhism and Jainism, with the evolution of Tantra, Bhakti and Shaktism, and into the modern era.

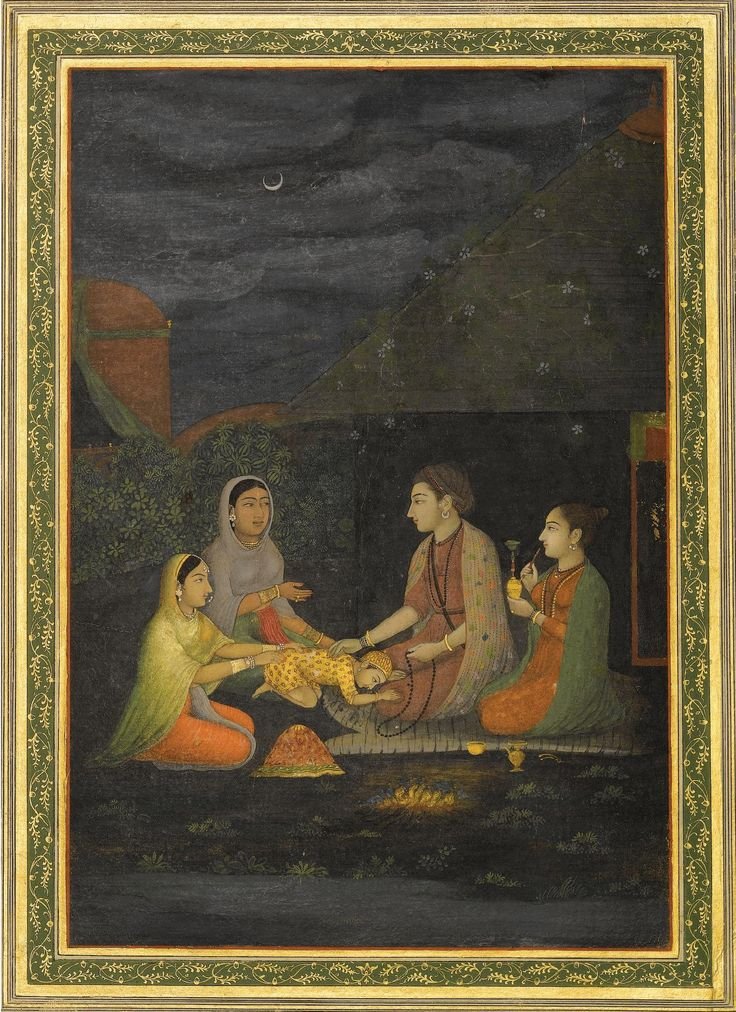

Two women and a small child visiting a yogi and yogini at night, Provincial Mughal, India, late 18th century.

Challenges of researching the lives of marginalised people

The challenges of researching the roles of women and of low status men relate primarily to the fact that their voices are not represented or heard within academic (or any written) sources. Written documentation of Vedic society chronicles an elaborate institutional religion, requiring significant material resources and social organization, privileged in its socioeconomic class, and owing their preservation to diligent oral transmission over many generations, spanning millennia. Many feminist scholars are of the opinion that no trustworthy gender research can be carried out on cultures we know only or primarily through institutional texts, meaning that it is necessary to apply a ‘hermeneutic of suspicion’, i.e. we need to read between the lines. As to the voice of the lower castes, their voices are equally, and potentially even more, difficult to hear; it is a universal truism that the pen that writes history is held by those who also hold the power in society.

The origins of the caste system

The Vedic period lasted approximately from 1500 to 600 BCE. It is associated with the earliest body of Indian literature known as the Vedas, and the social dominance of the Brahmin or priestly class. Little is known for sure about the societal structure or the religion of the Indus valley civilisations preceding this period, although the height of Harappan civilization was characterized by a highly developed urban culture and a script which is perhaps proto-Dravidian. The Harappans created large numbers of female figurative models, evidencing respect for and veneration of the female form.

Goddess figures from the pre-Vedic Indus valley cities of Mohenjodaro and Harappa

Beginning some time at the start of the second millennium BCE, a process of de-urbanization of the region began, marked by migrations of the Aryan people into the Indian northwest, bringing with them the beginning of the Sanskrit language. Their descendants expanded into new regions of the east and the south, bringing into its orbit new peoples, customs, beliefs, and languages. Migratory clan groups (‘jana’) evolved at the time, aligned by race with either Aryan or Harappan heritage. Some theorise that the Aryan invaders sought to preserve pure bloodlines by enforcing closed clan groups, evidenced by common physical characteristics within the caste groups that persist to the current day. Others are of the contrasting opinion that intermarriage surely soon wiped out any racial differentiation, and so the term ‘Aryan’ becomes a cultural and linguistic rather than a racial designation. Nonetheless, most agree that Aryan descendants composed the Vedic literature and constituted the dominant classes within Vedic society, appearing to lose all memory of that immigration by their ancestors.

Whether or not the memory of immigration was lost, during the Ṛgveda period, orthopraxy and the production and preservation of ritual poetry was in the hands of the separate lineage janas, the members of each tracing their patrilinear affiliation back to a common ancestor rishi. Towards the end of this period, the older clan structures deriving from any residue of racial allegiance gradually broke down and were supplemented and replaced by class (jati), and arranged into hierarchies. A lower class, responsible for animal husbandry and agriculture and, later, mercantile trade (ksatriya) is set below the priestly ruling class. This hierarchy began the division of society into hereditary groups with defined roles and relative superiority or inferiority.

A late 18th century painting of Saptarishi (the seven ancestor rishis) and Manu (the first man) from Jaipur, Rajasthan.

Vedic Brahmanism both shaped and shaped by the creation of the caste system

As is often the case with distant history, this all sounds like a natural, linear progression, but it must be pieced together from the Vedic religious texts. The fulcrum around which Vedic society pivoted was that of highly trained, high born, male Brahmin priests in separate patrilineal groups, the members of each tracing their lineage back to a common eponymous ancestor poet-priest, preserving orthopraxy and ritual, and writing it down.

After the Ṛigvedic period, the creation of the Ṛgvedasaṃhitā caused a redefinition of orthopraxy, and the lineages were superseded by the fourfold varna system. Social divisions were becoming sharper, with the upper varnas (brāhmaṇ, kṣatriya and vaiśya) having defined occupational function respectively as priests, as warriors and aristocrats, and as the providers of wealth through herding, agriculture and exchange. These three higher categories also had strict marriage regulations. A substantial change at this time was the introduction of the fourth śūdra varna, with these lesser clansmen designated as ‘units of labour’, and a fifth varna: the untouchable dalits.

In the PuruṣaSūkta hymn (from the Ṛgveda 10.90, although believed to be a later addition to the Ṛgveda), the brahmans described the spiritual unity of the universe, presenting the nature of the cosmic being, and that from his mouth, arms, thighs, feet the four varnas (brāhmaṇ, kṣatriya, vaiśya and śūdra respectively) were born. Being the mouth of the divine, the priestly class had authored a mythical sanction to the entitlements of their role. High caste Aryan Brahmans were simultaneously shaping Vedic religion, and their society around it; their lineages elevated them above the other strata of society, enabling them to take the rein of societal control firmly in their own hands, the hands creating the scripture.

Dogma also spiritually elevated the first three varnas to dvija (twiceborn) status, the second birth being ritual initiation; śūdras, with no access to ritual, had a single birth. Having so few rights in the hierarchy, the śūdra was a servant whose master could do with him or her whatsoever he wished, even kill him.

The brahmans continued to realize the significance of the social divisions; they took the opportunity to invest authority in their own caste, claiming the highest position in the ranking of ritual purity. While the kings were the patrons of the sacrifice, the brahmans gave themselves alone right to perform yajna sacrifice and initiation of kings. The varna system became a virtually infallible system of social control, with the Brahmins claiming rights to bestow kingship, kings controlling the vaiśyas and śūdras, and all men with the right to marry had control over their wives and daughters. This control over marriage and of the exchange and subordination of women was an essential for the continuation of caste society.

The lives of women and the lower castes in the Vedic period

The Vedic literature corpus was, for the most part, both produced by and intended for an audience of the Brahmanical elite, and so provides the main (although somewhat narrow) view into Vedic society. The corpus neither provides a complete view of the life of the general population outside of the priestly class, nor a female viewpoint. Transmission of the canon was oral, and while such traditions are often considered the ‘folky’, informal domain of women’s lore, Vedic Brahmanism by contrast required a highly structured organisation of priests with the economic leisure to denote the lives of countless people the task of being mnemonic automata, impersonal channels of transmission century after century. This economic leisure proscribed access by the lower castes to the religious scripts and the knowledge therein; the priestly class also explicitly excluded women.

The concept of impurity drove much Vedic dogma: śūdras were excluded from Vedic ritual, as they were deemed impure, as many worked in ‘polluting’ trades such as cremation. Women’s processes of menstruation and childbirth were also deemed polluting, giving women an innately impure nature, requiring their control and protection by a male authority. Almost universally, women are culturally associated with impurity and danger, and control and misogyny arises, as in Vedic Brahmanism and Buddhism, as a response to this danger. Consequently, women were at best ignored by the Vedic religious framework, only having relevance in their relation to men, as wives, mothers, or daughters. Women’s lesser status was explicit in the Vedic corpus, for example:

The wife is a friend, a daughter brings grief, but a son is a light in the highest heaven. - Aitareya Brāhmaṇa 7.13

A man was even permitted to take a second wife if the first was unable to bear a son. Vedic dogma was full of irreconcilable incongruities, however, as a man was ‘incomplete without a wife’:

A full half of one's self is one's wife. As long as one does not obtain a wife, therefore, for so long one is not reborn and remains incomplete. As soon as he obtains a wife, however, he is reborn and becomes complete. - Satapatha Brāhmaṇa 5.2.1.10

While śūdras and women shared similar lack of status, the wives of kṣatriyas and vaiśyas had one advantage: Vedic ritual was centred around the married householder and his religious duties of offering sacrifice and of procreation. Herein lies women’s access to status: the householder’s wife was obviously key in procreation, but she was also considered an equal half of the householder ritual, with specific duties that could not be performed by anyone else. Correct performance of ritual was an obligation to the householder, from which he was only absolved by death, in order to attain heaven and immortality. Rituals were elaborate, expensive and required considerable time to be dedicated to them: the agnihotra fire sacrifice was a daily requirement, and additional sacrifices were required on special occasions in the ritual calendar. Only those with the luxury of time and wealth could have had access to this level of religious dedication.

Women may have had an even more pivotal role in Vedic society than the corpus states explicitly however, due to their forging of alliances through marriage, and their mediating role between men in social occasions, and between men and the Gods in ritual. Women’s agency, which on the surface reading of the text appears so absent, can perhaps be found by reading between the lines regarding the necessity of women in the rituals, particularly domestic rituals, and as an accidental by-product of the negotiation of the conflicting male religious goals, those of sexual restraint, while still needing the legacy of sons. As has often happened throughout human history, women were the bearers of paradox in ancient India.

The Emergence of Asceticism and the Śramaṇa religions

Asceticism would seem to be a challenge to the integrity of Vedic society, with its normative ritual sacrifice built around the central edifice of marriage and the householder, but there is evidence that ascetic practices flourished in northern India at least as long ago as the first millennium BCE. Indian asceticism is linked with two different religious traditions: one of Vedic origin, with a focus on renunciation and obtaining superhuman power (siddhi) through austerities, the other being non-Vedic, and using practices of meditation and abstinence from activity to gain saṃsāra (release from rebirth). As women and low caste men were forbidden from performing Vedic sacrifice, they were not presumably in a position to renounce it; a solitary, itinerant lifestyle might also be unappealing to women, not least for reasons of safety. That said, there is evidence for women having adopted asceticism. The reason may have been less of a religious choice and more perhaps for social or economic reasons, for example leaving an unhappy marriage, or being widowed. If the subsequent Śramaṇa religions arose out of a wish to rebel against the elitist hierarchy of the Vedic Brahmanism and offer more religious access to lower castes, they certainly did not offer any more equal opportunities for women. Cross-culturally, ascetic texts are notorious for misogynist attitudes; this is certainly the case with early Buddhist literature, the Pali Canon having many references to women and their bodies as shallow, loathsome and disgusting.

The Rise of the Bhakti, Tantra and Shakta Traditions

With the later rise of the bhakti, tantra and shakta traditions, women and lower castes began to have greater access to and agency over their own religiosity. The 8th century CE spread of the Bhakti movement, prioritised love, devotion and surrender to God over the Sanskrit texts and the need for Brahman mediation. A first major step towards inclusivity and egalitarianism was the admission of both women and śūdras to be initiated into the tantric systems. In the shakta traditions, many religious texts prescribed respectful treatment of women, women having the potential to be mothers, hence considered closer to shakti than men, and a blessing in itself. Women gurus were (and still are) preferred in some tantric schools. The first tantric role for women is to become a ritual incarnation of the goddess, to be offered worship. Rather than a fearful suppression of the ‘danger’ and pollution of women, tantra and shakta positively embrace menacing and powerful tantric goddesses and yoginīs. Further, a Shakta is described as any ‘person who worships, loves, seeks power from, becomes possessed by, or seeks union with any regional or pan-Indian goddess, and he or she is not disqualified by caste, worship of other deities, initiations, or level of education.’ Women appear as more important, even instrumental participants in shakta ritual. Bhakti, Tantric and Shakta traditions offered an about-turn from the misogyny of both Vedic Brahmanism and the Śramaṇa religions, and of Vedic social control.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the caste system evolved from an initial wish to preserve the integrity of racial groups under threat from Aryan migrants from the north-west. The migrants brought with them beliefs that became Vedic Brahmanism. Society evolved from the clan organisation to one of castes, and was shaped by the wish for the Aryan Brahmans to maintain power in the hierarchy over subordinate castes. With the PuruṣaSūkta they wrote into their mythology a justification for their own superiority. They gave themselves the right to nominate kings, who in turn could control the castes inferior to them. The time and wealth investments required for Vedic worship precluded low status people from full religious participation; śūdras have little voice or agency in religion or life. Vedic religion was truly a ‘Geertzian’ model both of society and for it.

The Vedic Brahman attitude to women was conflicted. In common with many other cultures, women’s processes of menstruation and childbirth were viewed as dangerous and impure, inspiring control and misogyny, as in Vedic Brahmanism and Buddhism. They were seen as required for procreation, and admitted, even required, as an equal participant in the sacrifice, while being described in the scriptures as valued less than sons and disposable if not able to produce male heirs. If the status of women in society is equivalent to commentary on that society, then Vedic society was certainly paradoxical. While the Śramaṇa religions arose in part in rebellion against the Vedic hegemony, and offered more social inclusivity for low status men, the theme of misogyny continued until both women and śūdras gained admittance to tantric, Shakta and bhakti practices, with powerful goddesses welcomed into the pantheon, and women even becoming key in Shakta ritual.

Did this change of fortune for low castes and women pave the way for an egalitarian modern India? Gloomily, caste continues to be a structural cause of inequality and poverty in present-day India. Many people in modern Shakta traditions still feel that they are oppressed by aggressors and colonialists who are not Western, but rather brahmanical Hindu. In the Puranic era DevīMāhātmyam text, goddess Devi arose to slay the demons that were threatening the earth. These demons may have been metaphors for the cultural threats to contemporary Vedic society, but the modern world faces even greater challenges to its very survival. Aurobindo Ghose said that if there was to be a future, it would wear a crown of feminine design. May Devi continue to rise, slaying the demons of inequality, for the sake of the earth and all Her people.

Devi portrayed as Mahishasura Mardini, Slayer of the Buffalo Demon, in the Devi Mahatmya.

Thank you for reading! If you would like to read more about why I am passionate about extending the accessibility of contemporary modern yoga practices to a wide audience, you might like to also read my blog post Yoga and Inclusivity.

References

Dhand, A.2008. Woman as Fire, Woman as Sage: Sexual Ideology in the Mahābhārata. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Dumont, L. (1980) Homo Hierarchicus: The caste system and its implications, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Feuerstein, G., Kak S. and Frawley D. (1995) In Search of the Cradle of Civilization, Quest Books.

Geertz, C. (1973) The Interpretation of Cultures, Basic Books: New York.

Jamison. S. (1996) Sacrificed Wife; Sacrificer’s Wife. Oxford University Press: New York and Oxford.

Khandelwal, M. (2010) Women in Ochre Robes: Gendered Hindu Renunciation. SUNY: Albany.

McDaniel, J (2004) Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls: Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal, Oxford University Press: New York and Oxford.

Mosse, D. (2018) ‘Caste and development: Contemporary perspectives on a structure of discrimination and advantage’, World Development, Volume 110, October 2018, Pages 422-436

Olivelle, P. (1993) The Āśrama System: The History and Hermeneutics of a Religious Institution, Oxford University Press: New York and Oxford.

Parpola, A. (2015) The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization, Oxford University Press: New York and Oxford.

Proferes, T.N. (2011) ‘Vedas and Brāhmaṇas’, In: Jacobsen, K. and Malinar, A. (eds.) Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol II, Leiden: Brill

Proferes, T.N. (2012) ‘The Vedic Period’, in: Jacobsen, K. and Malinar, A. (eds.) Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. IV, Leiden: Brill.

Thapar, R. (2002) Early India: From the Origins to 1300. Penguin: London.

Törzsök, J (2014) ‘Women in Early Śākta Tantras: Dūtī, Yoginī and Sādhakī’ in Cracow Indological Studies Tantric Traditions in Theory and Practice, Vol. XVI, pp. 339-367